| Staying power, strength, eternity. It all seems so permanent, so strong--it's "set in stone." Actually, we know that's not really true; it's matter of time and perspective. Rock is not so fixed. It can be breached; it moves. It falls down, it cracks. Moss and lichen are constantly eating it away. Mountainsides reduce to pebbles, and eventually, sand. |

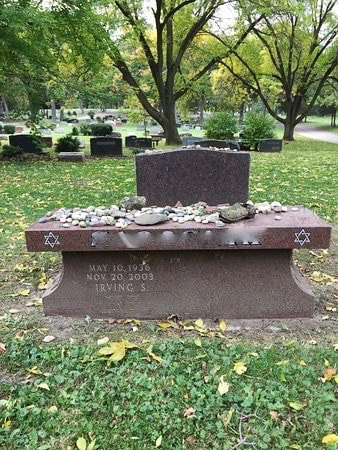

For those unfamiliar with the custom, it is a simple concept. When a visitor comes to a gravesite, he or she leaves a small stone to essentially say, "I was here, and I remember you." The stones are typically pebble-size, but this does vary, and as my images show, sometimes other materials supplement or replace the stones now--pretty pieces of glass, shells, even beads. They accumulate over time, and clearly, if one encounters a memorial marker covered with a large collection of small stones, it indicates how much the deceased was loved and appreciated. One description I read of walking in the military cemetery of Jerusalem, mentions "heaps of stones, like small fortresses" on the graves of fallen soldiers.

Stones may not be eternal, but they last longer than flowers, and do not fade. They give a sense of solidity and allude to the permanence of memory. The origin of leaving these stones is not completely clear, although there are many stories. One I like --although it may well be apocryphal-- is that flowers were originally left at graves to cover up the smell of a decaying body, but because Jews were traditionally buried within 24 hours, the flowers were not needed. Stones were, again, a longer lasting offering. A related idea is that living people like the smell of flowers, but the deceased are beyond that--they are one with God and no longer need such temporary pleasures. There are also stories about stones helping to keep the soul of the deceased from wandering, about laying down arms in death (symbolized by laying down the rocks), and shepherds tracking their sheep by representing each with a pebble. One particularly poetic explanation is that a headstone symbolizes the soul of the deceased (remember, there were not always headstones--just piles of stones that might keep a wild animal away from a recently buried body), and when a visitor leaves a stone, it symbolizes their own soul and the way all is "tethered together in mitzvah [good deed, blessing] and metaphor."

Other than remarking on an interesting practice, I am impelled to write about these memory stones because I've been feeling the energy of rocks so strongly. It's hard to write about; it's a feeling, an intimation about something. It is not a concept. I tried to capture some of it with my poems and images of the rocks on Mt. Shasta (August, 2018), and it has to do with the rocks holding the holographic imprint, holding memory, but maybe a much longer, deeper memory than we even know. Not exactly really permanent, but so long-lived by our standards that it comes close. Discussions of the Jewish custom of leaving rocks keep referring back to the Bible and the rocky landscape that was part of Jewish history. The stone on which Abraham was to have sacrificed Isaac is referred to as hashityah, the foundation stone of the world. A pile of stones could be a sacred place, a place of prayer. Moses sat on "the Rock," and carved the tablets from it. Jacob's Ladder rose from a stone. On the darker side, people were stoned to death, and "stony" implies unyielding, cold, and without empathy.

I was very moved recently in driving through the Atlas mountains in Morocco. This is a dramatic region, all about rock and stones. The terrain consists of stones for miles and miles and miles, sometimes pebble-sized, sometimes big boulders. Houses are built of stone. Stone tumbles into rivers. Sheep and goats climb over high stony peaks. I kept sensing the stone memory, the consciousness held in all that rock, but I couldn't really access or translate it. I felt stone-ness, but there are no words or concepts to say what it was I felt. At one point one of my traveling companions remarked that she wouldn't want any of that "real estate"--it was too much relentless rock, too hard to deal with, too unfriendly. Rocky terrain=trouble. I reacted almost viscerally; yes that's true, I thought, but you aren't asking what the stones know, you aren't feeling into the stone or the stone space. Maybe those who live here live deep in the stone, know what the stone knows, hold stone memory. Maybe the rock remembers them. Maybe they have another, silent experience that you can't even imagine.

Maybe. Right now, today, I will hold some stones and breathe with them: round smooth ones tossed by Lake Michigan, and sparkly ones from riverbeds in the high Andes (another oh-so-rocky landscape). I will even touch the very fine sand I brought back from the Sahara--sand that was stone, ground down to the consistency of fairy dust. Maybe I will breathe them in, absorb their stone wisdom. Maybe I will be taken into the secrets of stone.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed