5.75" high

Tie-dyed felt fabric, freshwater snail and clam shells

Mollusks dream deep in the water, silently witnessing: flitting fish, waving weeds and water lilies, darting dragon flies, the heron, the swooping swallows, kayak paddles, gull shadows.

I had been gathering the tiny bleached snail shells that rose to the surface of the lake for many years, reaching down from my kayak into the weeds and water lily pads to collect them. I never saw the living snails, but knew they were abundant, as there are shells all around the shore. These white housings are fragile, easily crushed between thumb and forefinger or by accidentally applying pressure. There’s always sand in them when I clean them out, for first they sink to the lake bed (where most often they must themselves become part of the sediment), and then float up to the surface when they are light enough. Sometimes there are remnants of the animals that built these shells, just tiny filaments of dried-out flesh that look much like tendrils of weeds that got stuck inside.

After I had been paddling the lake for decades, local conservationists made a great effort to remove the alien carp, which had been drastically changing the natural eco-system. The carp churned up the bottom and thus clouded the water, keeping visibility low. (Big carp were literally caught in nets through holes in the ice in the winter! and they were prevented from spawning in the spring). When the water cleared, I caught sight of large clam shells on the sandy bottoms in some of the shallowest areas. I was extremely excited, for I had not realized they were there at all. (I knew of freshwater clams and mussels in the nearby rivers, but had no idea there were clams in my figurative backyard.) It was a revelation, and seeing them was still a rarity. I proudly came home with several clam shells that year.

The next season, with the water even clearer, I spent time trawling for clams. I spotted more shells in a different area of the lake, and then started to see live clams, usually positioned vertically, with just the muscle/foot peeking out of the sand. Once you know what to look for, of course, they are more abundant than you had guessed.

If uncertain whether or not the clam is alive, I pick it up, and if it is, it very quickly closes up to protect itself. This feels like a real encounter, a chance to for me to understand what I am holding as more than a shell--as a fully living, sentient creature, with its own needs and preferences and its complete life that has nothing to do with me. I always put living clams back. (Note: The lake has clouded up again over time, so these encounters are rarer again now)

Spending a fair amount of time in what I have come to think of as “the clam beds,” I also became very attuned to the underwater life in that sandy area. I discovered the amazing phenomenon of fish nests, holes or depressions hollowed out in the sand for female fish about to lay eggs. I am not sure what type of fish does this in Lake Wingra, but it could be a bluegill, perch, bass, or possibly even that much-feared carp. The circular depressions are visible only early in the kayaking season, since the nests are made in the spring, for spawning. They call these kind of nest-makers the “pit-diggers. From what I’ve read, it’s often the male who actually makes the nest. He chooses a good site (the ones I have seen are all free of weeds) and then swimming in circles, vigorously fans out the sandy bottom with his tail and ventral fins. The nest is a conical depression. An old New York Times report about the sunfish and bream that make nests of this sort indicated their nests are about 12-14” in diameter and 4” deep. The ones I see are about that wide, but a bit deeper.

When the nest is ready, a female deposits her eggs, which the male then fertilizes. In many species, the female takes off, leaving the male to guard the nest until the hatchlings emerge. The hatching period can last a month, and during that time bigger fish and other predators have to be fought off.

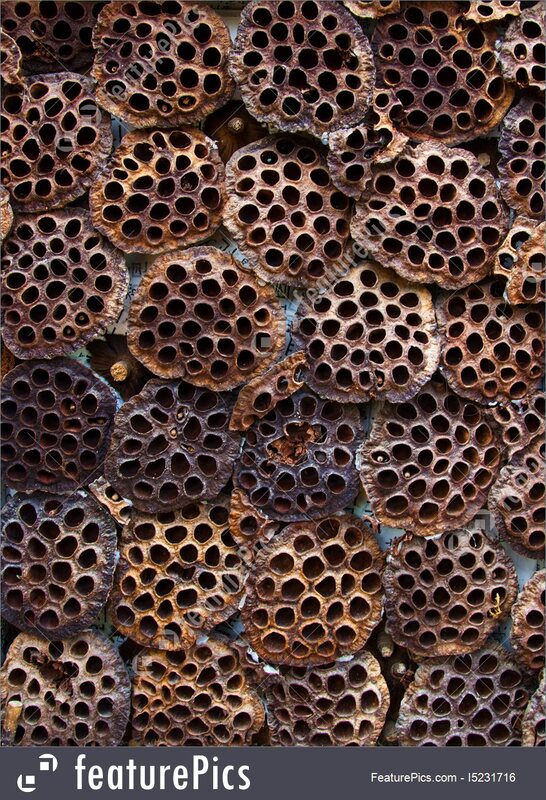

A similar kind of discovery came about in approximately 2011. That August, I came upon a patch of lotuses in a particularly shallow end of the lake--an area where upright flowers were pushing up among distinctly round, non-waxy looking leaves that typically held themselves above the water surface. These were definitely not water lilies. I had thoroughly explored every area of this lake, and lotus plants had never been there before. How did they get there? I was excited, for I knew about lotuses, both from their symbology in Buddhism and from their role in biomimicry as a design inspiration. By observing the way water sheets off the lotus leaf--the leaves are said to be self-cleaning because the water and dirt never sticks to the surface--people discovered ways to mimic the physical structure of the plant and devise other self-cleaning substances, such as paint, glass, and fabrics.

They always bring me back to the lake, and they always make me smile.

Heron tracks in the beige sand,

ducks on a log, quietly preening,

brown on brown

with orange feet, lined up

gull flies in, stark white

with yellow feet and beak

blue sky in the water, rippling

sun gleaming, then covered by cloud

A large clam shell, unbroken,

waiting near the shore

Tiny silver fish jumping, for reasons unknown,

arcing above the water, glimpsed in a flash.

Strong paddling homeward

as evening comes on.

Heron standing guard

as ducks preen

Blackbirds cry at cranes.

Muskrats draw lines with their bodies,

swimming straight.

Abounding green: duckweed, cattails, lily pads.

Swallows and damsel flies

add flashes of blue.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed