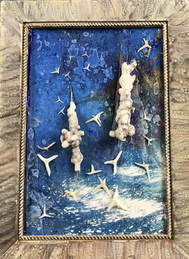

RISING FROM THE SEA

Mixed media construction: Altered paper, sea squirts (white crust tunicates), porcupine fish spines.

2016.

Like stars rising up out of the ocean… the elements of this piece are amazing, worthy of deep contemplation. When I was handling them I was indeed holding infinity in the palm of my hand (thanks to William Blake, “Auguries of Innocence,” for that phrase.)

A sea squirt (tunicate) colony that reminds me of rock candy. It’s an invasive colony growing on a suspended oyster growing device called a French tube, in Drakes Bay, Point Reyes, California. Photo from The Coastodian, March 2014.

I didn’t have to do anything to the tunicates, but there was a long process involved in extracting the other material, the tripod-like pointed forms, which are spines from the skin of porcupine fish. (These are sometimes erroneously called pufferfish, but they aren’t exactly the same.) I first discovered a washed-up specimen of a bulbous, prickly-looking creature on the Pacific coast of Mexico. It looked both faintly comical and frightening; the inflated body felt like an over-inflated balloon, but the spikes were formidable. I discovered these two features were the very characteristics of the way this animal defends itself; when threatened, it inflates itself to three times its normal size by sucking or pumping in extra water. Its stomach, which is pleated, expands to nearly a hundred times its original volume. Biologist Beth Brainerd observed the amazing structure of these pleats -– there are folds within folds within folds, down to pleats so tiny that they can be seen only through a microscope. (It’s like a fractal--isn’t this the way form keeps going, in our bodies too…)

I was immediately interested in the spines—beautiful white external bones, almost begging to pulled out. I started with brute force—tugging, trying to extricate them from the skin, but they wouldn’t budge. I didn’t yet realize the ingenious structure of the spines, or the two layers of skin they stitch together. I soaked the skin, making it somewhat more pliable, and with great effort and snipping, slowly retrieved them, one by one. I admired their tenacity. Removed, they were like trophies, and I loved just looking at them, at their smooth, plastic-like surfaces and their satisfying shapes. It was especially lovely to take in the different sizes and how they each grew to fit their position on the animal.

This still wasn’t going to help me get them out of an intact fish. I put one in peroxide to soak and of course it bloated out, got soft. As it rehydrated, I was able to really see its patterning—to take in its stripes and the false “eyes” on its back.

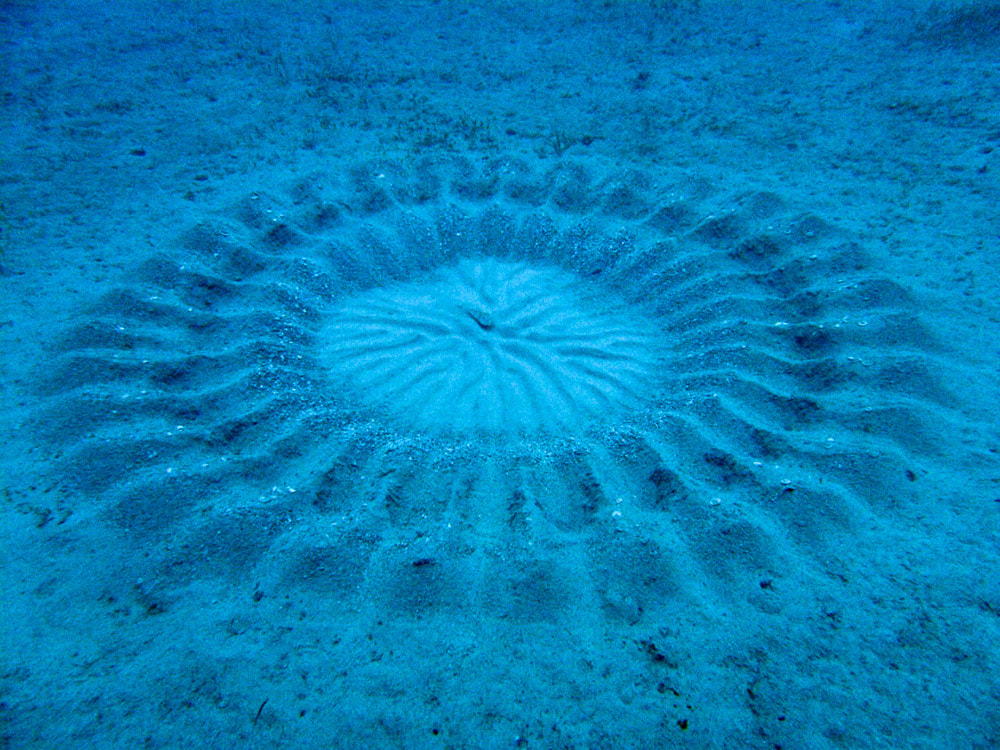

The most astounding part of the story just came through recently in an excerpt from a BBC-Earth documentary that was posted on YouTube. In 1995, divers noticed a small mandala-like circular pattern on the sea floor off Japan. It was mathematically perfect, and nobody knew what it was. Once they started looking, they discovered similar circles nearby. The mystery was heightened by the fact that they came and went unpredictably, and they reminded observers of crop circles, though they were completely underwater.

I have actually been slow to find ways to incorporate the porcupine fish spines in my work; their shapes are challenging to work with effectively. I do not want them to appear as they would on the fish, as I want the beauty of the whole tripod-like shape to be visible, rather than just the tip. (It’s as if I must peel away the skin for my audience, much as I had to do in processing the material.) Many of the spines I have are very small and delicate, and almost fly out of my hands when I try to handle them. In Rising From the Sea, that delicacy works well with the impressionistic forms of the background and the solidity of the tunicate.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed